Back in 2013 I came across a story online about the imminent arrival of what was then Bangkok’s newest mall, Central Embassy. The article’s comments section was overrun with jaded remarks by western expats:

“Another mall? The central business district of Bangkok is already overflowing with malls and shopping centres”, said one.

Another responded drily, “I was only saying last week how there are not enough shopping malls”.

In the intervening three years Bangkok has seen the opening of even more shopping centres, including Phrom Phong’s super HiSo EmQuartier and the Central Festivals at Westgate and Eastville. Several more malls have undergone massive renovations.

The ultra-luxe Central Embassy

One could sympathise with any Thai hostility to this relentless mall-building. Thailand is a Buddhist nation and the most religious country on the planet according to a survey carried out by WIN/Gallup International. It would be a surprise if the adherents of a religion which so deeply values asceticism had zero objections to the construction of buildings whose raison d’être is to facilitate desire, a primary cause of suffering according to Buddhist teaching.

But while all this mall-building has been going on I’ve been paying attention to what western expats say, and while your mileage may vary, my experience has been that their opinions tend to mirror the negativity of that three-year-old comments section.

What explains this consensus? We could start with statistics published recently that reveal the electricity consumption of Bangkok shopping malls. They showed that several Bangkok malls use more power in a year than whole Thai provinces, provinces that have upwards of half a million people.

If ever there was a statistic to reveal inequality in Thailand, that is it.

Facts like this make westerners obsessed with the equal distribution of wealth and resources uncomfortable, even if they are the reality of life in the developing world.

Whatever westerners may or may not feel about malls, Thais love them.

The photo-sharing social media app Instagram keeps records of the most photographed places on earth. Few will be surprised to learn that number one is New York’s highly photogenic Times Square. Move down the list and one finds other tourist favourites like Tower Bridge in London (#2), the Eiffel Tower (#3), Moscow’s Red Square (#4), the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco (#10), and the Colosseum at Rome (#13), until finally, at number 19, Thailand makes its first appearance.

Is it the stunning Grand Palace? Nope. How about the famous Reclining Buddha? Try again. Backpacker Mecca Khao San Road? Strike three.

Siam Paragon. By Mark Fischer (CC BY-SA 2.0 licence)

The most photographed place in Thailand is Siam Paragon, a luxury mall. But if it’s hard to imagine a shopping centre being the most photographed site in Paris or New York, it’s probably because malls are dying in the West.

Google “dead mall” and you’ll find article upon article in publications like Time, The New Yorker and Forbes, all chronicling the sad decline of the American mall. Of the largest malls in the world, America’s highest entry comes in at number 30. Western Europe’s biggest is even further down, at number 60.

Why is the mall dying in the West? Some blame can be attributed to the increasing popularity of online shopping, a phenomenon which hasn’t reached its full potential in Thailand. But culture has played its part, too.

When malls first appeared in the United States in the 1950s they were considered wholesome and convenient places for suburban families to spend time in. For three decades until 1990 they enjoyed almost uninterrupted growth. Mall-building peaked in the United States that year (they built 16 of them), but the mall has been in a downward spiral ever since.

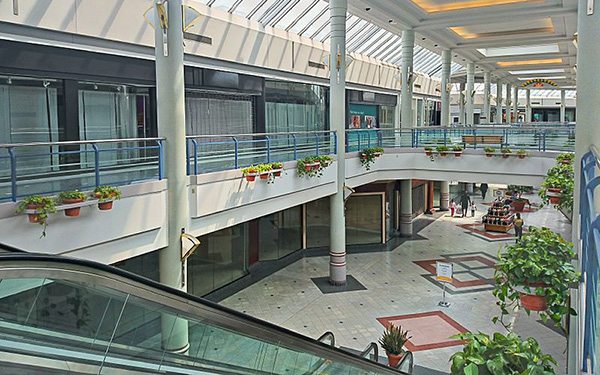

The languishing Landmark mall in Virginia. By Payton Chung (CC BY 2.0 licence)

Readers who grew up in the 1980s will remember a number of American movies featuring pivotal scenes set in malls, most notably Dawn of the Dead (1979), Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982), Weird Science (1985), Commando (1985), and Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991). A few stragglers like Clueless (1995) and Jackie Brown (1997) came along later, but in recent years the mall has been largely absent from the silver screen, perhaps a reflection of America’s falling out of love with the humble shopping centre.

Certainly by the turn of the millennium, malls were synonymous with suburbia. This was the kiss of death; the suburban milieu is not highly regarded by cultural elites. Malls were perceived as places where teenagers hung out and drank milkshakes.

People didn’t go to malls to buy first editions of Ulysses or listen to Berlioz concerts or eat foie gras and blue lobster ravioli. They went to eat cheeseburgers and watch Rocky IV. These snobby attitudes eventually trickled down to the proles, as they always do, and their views were compounded by the growth in popularity of concepts like farmers’ markets, organic food and “sustainable living”.

To the modern western consumer raised on a diet of Naomi Klein, Fast Food Nation and Michael Moore documentaries, there seems something crude — vulgar, even — about the shopping mall. The mall represents unfettered capitalism and unashamed consumerism in an era when such things are viewed as unethical if not immoral. When one’s material needs have been met, we climb up Maslow’s hierarchy to self-actualisation and become suspicious of consumption for consumption’s sake.

What kind of message are we sending our peers when we choose shopping in the suburbs over lunch at Michelin-starred brasseries, practising yoga, or teaching English to refugees?

Malls that have boutiques selling clothes manufactured by kids in Bangladeshi sweatshops, burger joints that tear down Brazilian rainforest to raise cattle, and stores selling overpriced American electronics on credit to people who can’t really afford them drive us mad with guilt, like characters in an Edgar Allan Poe novel.

For westerners, the guilt is everywhere. Whither salvation, then?

For The Woke Westerner™ salvation is to be found in artisanal shopping experiences.

We romanticise what we see as a Gallic style of shopping, wandering from store to store in walkable, picturesque villages. Despite its ostensible inconveniences, there is something charming about buying meat at a butcher, then strolling to the baker for a baguette before heading to the cheesemonger for some Brie and perhaps a cheeky glass of Port with the cast of Madame Bovary in the local bar.

The hallowed farmers’ market – “farm fresh”. By Allen Sheffield (CC BY 2.0 licence)

It is important to point out that walking, not driving, is an essential part of this fantasy for it affects one’s carbon footprint, the reduction of which is central to salvation.

This kind of fantasy is redundant in Thailand.

Unlike western malls, which tend to be located on the outskirts of towns and cities, Thai malls are usually situated in city centres. More importantly, the rustic shopping experience is but a chimera in a place like Bangkok. Thailand is a developing nation with infrastructural issues that simply don’t exist in most of the developed world.

Anyone who lives in Bangkok will know that even if the city were of dimensions small enough to making walking amenable, the broken footpaths and frenetic traffic would test the constitution of even the most patient of people. Bangkok’s enormous air-conditioned malls, filled as they are with everything one might need to enjoy a day’s leisure, are Thailand’s substitute for the town centre.

Pay attention to the things that are inside Thai malls and you’ll understand what I mean.

Where I’m from, the serious bookshops are in city centres. In Thailand the biggest bookshops are in malls.

Most malls in the West are about shopping and little else. In Thailand they are as much about eating, if not more, with vast floors devoted to dining. I never saw a bank in a mall before I moved to Bangkok. The idea of using a bank in a mall where I’m from is preposterous, but since I’ve lived here I wonder why we don’t do it back home, too.

In addition to providing services that don’t exist in malls in the West, Bangkokians have to find ways to circumvent the extreme heat of the city, Bangkok being the official hottest city on earth.

Just imagine walking around a hypothetical village in Bangkok, window shopping, for hours. It sounds like hell. The mall is an attempt to make it possible, a place for people to take care of business or just hang out with friends and family, shopping and eating, in a pleasant, 23 degree environment.

A typical Instagram post tagged at Siam Paragon

It is easy to be cynical about mall culture, but malls here are more than just cathedrals of mindless consumerism. They serve a different purpose to their brethren in the West.

Their growth is not emblematic of capitalism’s nefarious tentacles smothering us, but in the face of ragged pavements, noise pollution, unyielding heat, and the second most dangerous roads on the planet, a sign of humanity yearning for community.

How do you feel about Bangkok’s mall culture?